Whenever you use your computer, phone or a "smart" device, you're creating thousands of little bits of information that can tell someone all about you. You don't always have a lot of control over who uses this information or what they do with it.

Knowing who might be invading your privacy can help you make informed choices to protect yourself. We're going to look at two of the most common ways your information is taken from what you do on your computer. The first is surveillance by government spy agencies. The other is tracking through websites and apps.

State Surveillance

The spy agencies of the US, UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand are gathering unbelievable amounts of information about what everyone does online.

The story of how this came to be begins 24 years ago. On September 11 2001, American Airlines Flight 11 and United Airlines Flight 175 were hijacked by Islamist militants and crashed into the World Trade Center in New York. Later that day, two more flights were hijacked. One was flown into into the Pentagon in Washington D.C., while the other crashed in a Pennsylvanian field when passengers fought back against the attackers. These attacks killed 2996 victims and injured up to 25,000 more. They covered New York in toxic dust and caused widespread panic. The attacks on 9/11 killed more people than any other terrorist attack on the US.

If you're older than 30 and you were living in an English-speaking country at the time, you remember the day well. The sight of two of New York's tallest and most iconic towers collapsing in fountains of dust and flame was unforgettable.

Things changed quickly. The US, Britain and other Western countries went to war in the Middle East. For the first time, many Americans thought of terrorism as something more than just something that happened overseas far away. It could happen in the places they lived and worked. Fear, suspicion and paranoia fell over the Western world.

9/11 was soon followed by laws to make it easier for spy agencies, such as the US's National Security Agency, to collect information in the name of preventing terrorism. It became possible for them to demand phone and internet companies hand over their customer's data and order them not to tell anyone. Billions of dollars were given over to intelligence agencies to use their new powers.

A few years later, there were rumours mass surveillance was happening. In 2006, a man working for the phone and internet company AT&T told newspapers about Room 641A in one of the company's facilities, which contained equipment useful for tapping into internet cables like the ones used to connect New York to the rest of the world.

But it wasn't until Edward Snowden shared some secret documents from the National Security Agency with journalists that people found out just how much spying was really going on.

They really are watching you: what was revealed in 2013

On the 6th of June 2013, UK newspaper The Guardian published the first article based on the files: "NSA collecting phone records of millions of Verizon customers daily". Over the next few months, more articles were published in different newspapers adding up to a massive conspiracy between the US, UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand ("Five Eyes") to spy on each others citizens. Other governments were also involved, including Germany, France and the Netherlands. Specifically, it was reported:

- The NSA collects data about the phone calls of the millions of people who use Verizon's phone systems, including what numbers are dialled, length of phone calls, and the time the call was made.

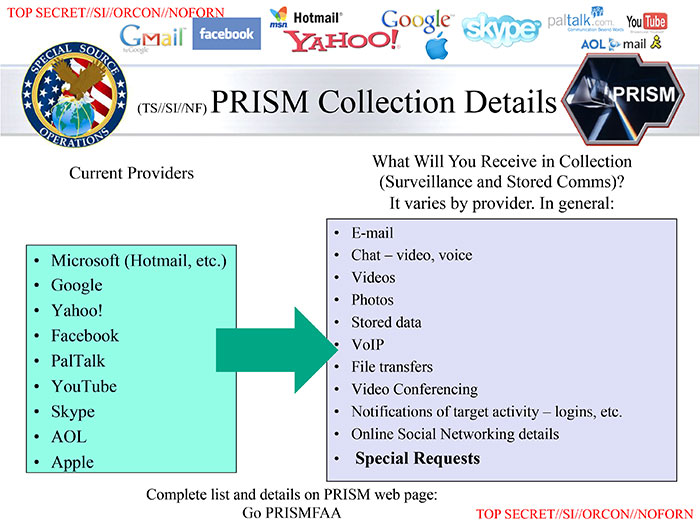

- The NSA and the FBI have forced some of the internet's biggest companies, including Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Apple, Yahoo and Skype, to give them access to their systems. This means they can get e-mails, files "in the cloud", phone calls and other data. (This program is called PRISM).

- The GCHQ (the UK's equivalent to the NSA) has direct access to what flows through the fibre optic cables that carry internet traffic around the world. It collects and stores a lot of this information without any one else knowing.

- The data Five Eyes collects could be searched easily without an order from a court. Talking about what's possible, Edward Snowden said, '"I, sitting at my desk, could wiretap anyone, from you or your accountant, to a federal judge or even the president, if I had a personal email". Files from the NSA used for training show that their software program, XKeyscore, could search the contents of e-mails, online voice calls, search and browsing history. XKeyscore was possible because back then most things on the internet at the time were sent over the internet in a form that let anyone read them.

This shocked people. People who worked for civil rights in the Five Eyes countries had been warning that terrorist attacks weren't very likely, that spies would use their new powers more than they needed to, and that stopping terror attacks wasn't worth the threat to people's privacy. Now it was here in black-and-white: Five Eyes was doing what everyone feared, and more.

It's been 12 years since the first article in the Guardian. The good news is that things have improved a bit. For one, most websites encrypt (or in other words, scramble) what you download before it gets sent to you so it probably can't be read by others. That makes it harder for the NSA and others to read the contents of what's sent over the internet.

However, we don't know what the NSA and others can do today; most of their work is secret. We do know the US Government has renewed the law that made the NSA's spying possible in the first place. The courts that would stop the NSA misusing its powers aren't something people in general can see into like normal ones. People who have worked with them say they give permission for spies to do a lot of what they want without any hassle. We should assume that mass surveillance is still going on.

Another problem is metadata. Metadata is "data about data". It's things like the addresses of pages you view, the account names you message, and the times you do things. Even though metadata isn't the actual contents of what people are doing, it still says a lot. If two people start calling each other, you can tell they have some relationship. If you look at a website address, you can tell what someone is interested in. For example, without knowing anything about the contents of this article someone who knew what web pages you were looking at could figure out that you're curious about free software and privacy.

Online Tracking

It's not just spies and the FBI that collect your data. Hundreds of companies are watching what you do when you use your phone or use the internet.

Now I don't have to say that what you do on your phone should be private. A lot of people would rather have their bank account emptied than have a stranger go through their phone. And yet, that's what's happening every day.

Spying on your phone or computer looks like many different things.

If you're in Europe or some parts of America, you will have seen pop-ups on websites asking you for permission to put cookies on your device. Cookies are small text files a web site can ask your computer to send back. They can be used like a label that's specific to your computer. When you visit a lot of websites, they'll include code from companies that specialise in collecting people's browsing history that asks for a cookie they put on your device. When you visit other websites with the same code, the company can connect the dots and can figure out where you've been.

Cookies were one of the earliest ways to follow someone around the internet. Eventually, people caught on and started blocking them. The companies fought back. They developed a way to recognize your unique browser without any cookie at all: browser fingerprinting.

This is how it works. When you load a webpage, your browser can give webpages lots of information about your computer. This might include what language you prefer, what your screen size is and what version your browser is. They might also run tests to see how your browser draws stuff. Because there's so much different information, it's very unlikely that lots of browsers have the same values for all of them. Just like a fingerprint, your browser is unique. There's only so much you can do against this.

Large platforms don't need cookies or browser fingerprinting to find out all about you. They can figure it out based on what you like, watch, read or listen to. The information they have on you might be used to make you spend more time on the app or advertise to you. In 2018, it was discovered that data from a personality quiz on Facebook was being used by Cambridge Analytica to target pro-Trump and pro-Brexit ads to those most likely to vote for them. You didn't have to even take the quiz: if only one of your Facebook friends did, your data would be taken by the company, too. 87 million people's information was taken this way.

Some apps might track you and sell your data directly. In 2017, the New York Times was given a file containing location traces of 12 million people. This location information was collected from a range of apps, including ones for weather or games. Based on the information, they were able to figure out who the phones belonged to and piece together what was going on in their lives. Apps that want to track what you're doing on your phone are helped along by non-free phone systems: both iOS and mainstream Android give your phone a unique advertising identifier that can be used like a cookie to figure out who you are as you use them.

Who wants this data and why

All this data is useful to lots of people. As you saw, the NSA claimed its data collection was for preventing terrorist attacks. Governments also use information for other reasons, not all of which are public. It can be useful for deciding government policy or enforcing laws, for example.

Political parties use this data to persuade voters. Information about what people buy, read, where they go or who they associate with can be useful if you want to tailor your message to someone. Most political campaigns, and some larger non-profits, purchase lots of information on people they can use to guess at how they might vote.

People selling products want to know who's likely to buy them. People who buy a particular product often have things in common. They might have gone to similar universities, work similar jobs and have similar tastes. If you know a lot about your customers, you can figure out what they might buy next.

Online advertisers use this to choose which ads they are going to show you when you're online. They can narrow down the people who see an ad to almost a handful who they know are most likely to have the power to vote on something or make a big purchase. Advertisers can even figure out what your mood is based on what music you're listening to and change what ads you see accordingly.

There are some less common reasons companies might want your data. For example, Amazon Alexa collects snippets of what you say around it and sends it away to make Alexa better at understanding you. A company that writes software might collect information on how you use it so they can figure out how to keep you using it for longer.

There are thousands of different uses for data. Unfortunately, not all of them are for people's own good.

Why you should be worried

Sometimes, when you talk about privacy people shrug and say they aren't embarrassed or scared about what's out there about them. But privacy isn't just about being embarrassed or ashamed. It's about the power we have over our own choices and our right to be treated fairly.

Anyone that has access to the data out there about all of us can use that information to find out what we fear and hope for in secret, what hurts us and what will make us change. They can manipulate how we feel, nudge us into spending more of our money and time on things we wouldn't want otherwise or influence us into supporting causes that aren't in our best interest.

If we're on the wrong end of government power, we might find our information being used against us. This is happening right now: in the US, ICE is using data from the same sources marketers use to help them imprison and deport immigrants. Surveillance also makes people afraid of challenging their governments and being curious about what's going on in the world. Soon after the articles about the NSA were published, there was a significant drop in people visiting Wikipedia's articles on terrorism and other sensitive topics.

If data's out there, it can be used by people that want to harm us. The same data that helps a company convince us to buy more bread can also be used by scammers and criminals to fool us.

And of course wherever there's lots of data, there's someone ready to steal it. As I write this article, data from Salesforce, which makes software companies use to record information about their customers, has been leaked online. Leaks like this happen every day.

How free software helps

Using free software will help preserve your privacy.

Free software is better for your privacy because everyone can control what it does. We can look at how it works and figure out if it's collecting information. When people put in features that are dangerous, they can be removed by others.

Free software also doesn't try to force you to make choices you might not want to. Non-free systems like Windows try to make it hard to protect your privacy. For example, Windows does its best to get you to save your documents on Microsoft's servers, where there might be a system like PRISM ready to read them.

Unfortunately, free software can't save your privacy completely. A lot of the information spy agencies and companies collect will be gathered even without you using a computer. You can't hide what URLs you look at or who you call even with a fully-free system. A lot of data is collected when you do things in everyday life, also: the supermarket might be selling data about what you buy; the number plate reader by the motorway exit might be following you as you drive around town.

But even if free software can't give you perfect privacy, it's still a big part of the solution. We just need to be aware of what it can and cannot do.

Being watched

One of the worst things about surveillance isn't about politics or marketing. It's about what being watched does to us as people. People who feel the eyes of others on them stop doing the things that make them special. They don't speak their minds, they don't take risks and they don't fight for what has to be defended. When we're all being watched, we lose the freedom to be who we really are and protect what matters to us.

Even though knowing we're being spied on can be disturbing, we can't let it let terrorise us. We have to keep on doing what makes us, us -- even if someone's watching.