Meet GNU/Linux

Neither Windows or macOS are free software. Both of them force you to give up your privacy and control over your computer.

Fortunately, free software developers have your back. Instead of Windows or macOS, you can choose GNU/Linux. GNU/Linux is based on free software: software from the GNU project, the Linux kernel and lots of other bits and pieces as well.

GNU/Linux -- you might sometimes see it just called 'Linux' -- is something called an operating system. The job of an operating system is to turn your computer from a worthless pile of silicon and plastic into something you can run useful programs on.

GNU/Linux comes in many forms called distributions (or distros). In this article we'll be exploring Trisquel, a distribution of GNU/Linux that contains only free software. You can find out more at https://trisquel.info.

What you'll need

First, have you made copies of any data you don't want to lose and put them in a safe place? If you haven't, do that now. Trust me, teachers aren't impressed when you tell them you accidentally deleted that essay you were meant to hand in.

You'll need to have just two things: a flash drive you can erase and a computer you want to run Trisquel on. It's easiest if you pick a computer that used to run Windows. Trisquel won't run on a lot of Apple computers.

If you can get a friend who already uses GNU/Linux to help you, you can ask them to copy Trisquel to your flash drive for you. If not, then you might also need to borrow a computer with Windows 8 or later on it. You'll need to be able to run programs from the internet on it, so don't use a computer at school or the library.

If you can get one, you might want an old junker for messing around with to stay on the safe side. You're unlikely to do any damage by playing with GNU/Linux, but maybe you're especially accident prone. Who knows?

Some bad news: hardware

OK, so I have to be straight with you: fully-free GNU/Linux distros only work with some hardware.

This is because free software authors need information about how the hardware does its thing to write code that'll work with it. Hardware companies often want to keep that information secret! Even worse, for some things, like Wi-Fi, the hardware that works is old. Like, seriously old -- maybe as old as you!

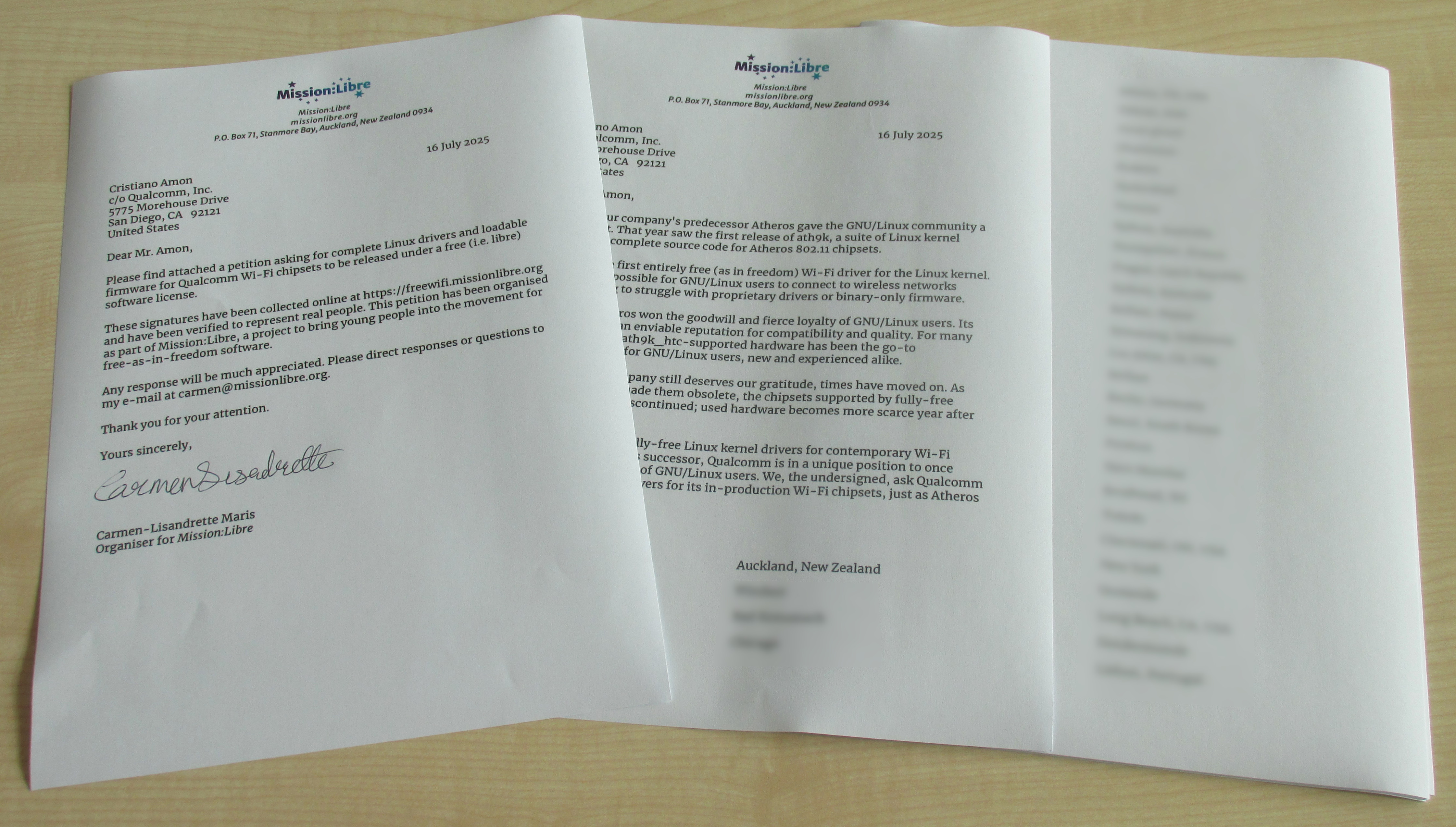

Earlier in 2025, Mission:Libre tried to make things a bit easier by asking Qualcomm, a company that makes Wi-Fi hardware, for fully-free software that  will work with their products. As I write this, I haven't heard back yet. I hope that by the time this article is in your hands there'll be good news.

will work with their products. As I write this, I haven't heard back yet. I hope that by the time this article is in your hands there'll be good news.

You can learn more about why so much hardware doesn't work with free software and see what we asked Qualcomm at https://freewifi.missionlibre.org.

Sometimes you have to make sacrifices for freedom. In later issues, we'll talk about what you can do when free software can't do something, and how you can help change things. But for now, let's play!

Getting Rufus and making a Trisquel disk

To run Trisquel without making changes to your computer, we're going to copy it to a flash drive and tell your computer to start from it.

It won't work if we just copy it like any other file, though. Instead, we're going to copy it using a program for Windows called Rufus.

You can download Rufus from the author's site at https://rufus.ie/en/. You want to download the file 'rufus-4.9p.exe'.

You'll also need a copy of Trisquel. You can download it from https://trisquel.info/en/download.

After everything has downloaded, it's time to make our disk.

Remove any other flash drives from your computer and plug in the one you want to use. Open the folder where you downloaded Rufus and double-click to open it. Windows will ask you if you really want to run the program. If it says 'Akeo Consulting' signed it, click yes. If not, stop now, delete the program and download it again.

Rufus looks complicated, I know. But there's only three things you need to do:

- Under the menu labelled 'Device', choose your flash drive.

- Click on 'Boot Selection' and open Trisquel's file.

- Click start.

That's all.

Rufus will start copying Trisquel to your flash drive. This can take a long time. While you wait, why not fill the time by reading some of the other articles in Libre!?

The hardest part: getting your computer to boot from the flash drive

OK, this is going to be a bit tricky. We need to tell your computer how to start from the flash drive, but different computers need to be told in different ways. If you know the model name of your computer, now would be a good time to search 'model how to start from usb drive'.

If you don't, we're going to have to experiment.

Boot up your computer. If you see your computer manufacturer's logo and some text, see if something says 'choose boot device' or 'boot from UEFI USB drive'. Reboot and quickly start pushing the key it says over and over again. If a menu appears, use the arrow keys to select the flash drive and hit enter to start. If it worked, you should see Trisquel start.

If you still haven't figured out how to get it working, try checking out this article: https://www.hp.com/us-en/shop/tech-takes/how-to-boot-from-usb-drive-on-windows-10-pcs. Its instructions will work just as well for Windows 11.

We're in: hello Trisquel

Whew, that was rough. If you're still with me, well done!

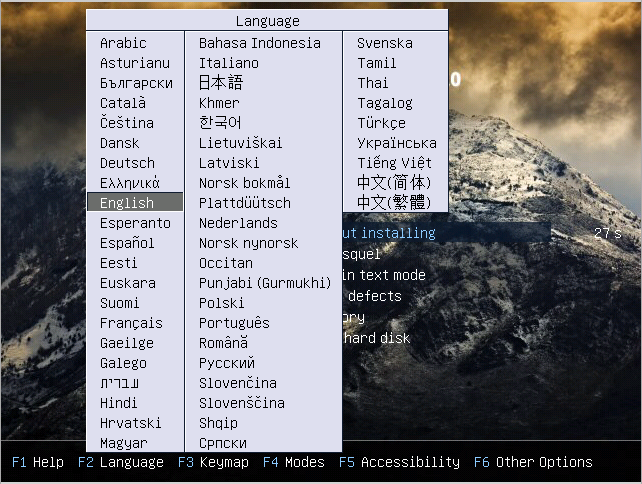

You should now see the screen above or to the left. Press 'Enter' twice to start Trisquel in English. The menu will vanish and you'll see Trisquel's logo pulse on screen for a while as it loads. It shouldn't take too long. If everything is working, Trisquel's desktop will appear.

If there's a problem, Trisquel's logo might stop moving or you might see the words 'KERNEL PANIC' on screen. But there's no reason for you to panic. Just try another computer or go back and make your Trisquel disk again.

Welcome home

Feeling a little déjà vu? If you're used to Windows, I'm sure you're feeling pretty much at home already.

Let's explore a bit. Double-click on the desktop icon that says 'trisquel's Home'. This will open your home directory. Directories are what we call folders on GNU/Linux. Your home directory is more or less GNU/Linux's version of the My Documents folder on Windows. Most of the files you make get stored here.

When you started the computer, you were automatically logged in as 'trisquel'. Your home directory is usually named after your username.

Look for a box that looks like the one below. Click on the pencil icon beside it.

![]()

Just like in Windows and macOS, directories can contain other directories. The only exception is /, the root directory, which contains all the others.

/home/trisquel is something called a path. A path tells you where a file or directory is starting from /. /home/trisquel means 'trisquel is in home, which is in /'

Click the arrow above the location box twice to see what's in /. All those directories contain different parts of your system. Some of the most useful ones to know are:

- /boot: information your computer uses to start, including /boot/vmlinuz, the Linux kernel. (A kernel is the part of an operating system which helps programs talk to hardware and share the computer's resources).

- /usr: many programs and files needed to make them work

- /etc: files containing settings for everyone who uses the computer.

- /media: this is where you'll find disks you plug into your computer (GNU/Linux doesn't use drive letters like C:\).

Let's try the command line!

Before there were windows and mice, there was another way of using a computer -- the command line. To use the command line, you type your commands in on your keyboard and your computer answers you by writing back.

You can use GNU/Linux without ever touching the command line, but experienced users are usually comfortable with both it and the mouse. The command line is easier and faster for a lot of things.

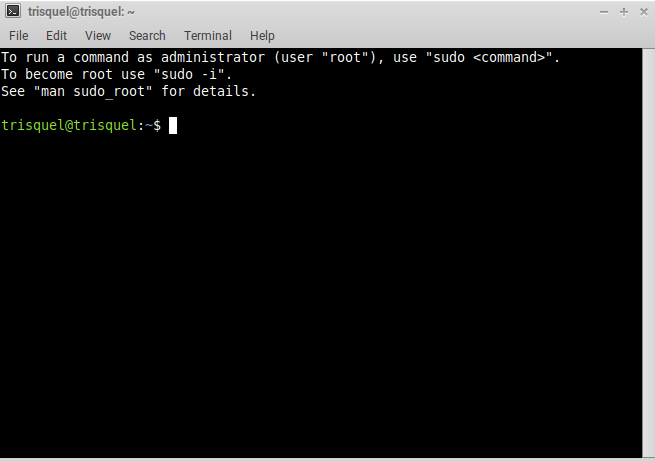

You can open the command line using the Trisquel menu. Look for 'MATE Terminal' under Accessories.

Take a moment to look at the window. Can you see a line that says 'trisquel@trisquel:~$'?

Let's break down what this means:

- trisquel: the username you're logged in as.

- trisquel: your computers 'hostname' -- the name other computers call it. This is also trisquel.

- ~: ~ is short for your home directory. This is telling you you're currently 'in' /home/trisquel. If you're in a directory, you only need to type the names of files or directories instead of their full paths.

- $: tells you the computer is waiting for you to type.

What's a terminal?

Very roughly, a terminal is a device with a screen and keyboard that's connected to a computer far away.

Terminals were used back when computers were so big and expensive that most universities and companies would only have a few of them. A bunch of terminals could let dozens of people share a single computer without needing to leave their offices.

'Terminals' on GNU/Linux are actually terminal emulators (an emulator is a program pretending to be something else).

Our first commands

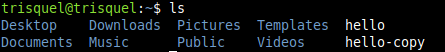

Our very first command is going to be ls. ls lists what's in a directory.

Let's try it. Type ls (no capitals!), and then press enter to tell the computer you're done.

ls will show you what's in your home directory. When ls has finished, your prompt will come back waiting for you to type again.

There aren't any other files in our home directory right now. How about we make one? Type echo "hello, world" > newfile and press enter again like before. echo is usually used to put words on the screen. The > tells echo to put its output in a file instead.

Now try ls again. You'll see your new file in your home directory.

More fun with files

newfile isn't a very good name for our file because it doesn't tell us what's in it.

In GNU/Linux, you can rename or move a file with the mv command (you might have guessed it's short for move!). If we want to rename our file hello, we type mv newfile hello.

Try it, then check it's still the same file by typing cat hello. cat will show what's in the file on the screen.

hello is clearly a very important file. We should make sure we have a second copy, just in case.

Let's make a copy by typing cp hello hello-copy. If you type ls again, you'll see both files sitting happily in your home directory.

We might want to make our copy even safer by putting it in its own directory. Type mkdir copies to make a new directory to keep it in.

Moving a file's location is just like renaming it. We can type mv hello-copy copies and mv will figure out what to do. If you want to see what's in copies, type ls copies.

Finally, when we're done with our copy, we'll want to get rid of it.

The command to delete a file is named rm. Obviously, we want to type rm hello-copy, right? Well, no. That won't work because hello-copy isn't in our current directory any more.

We need to tell rm where it is. We can do this by putting the directory name in front. Type rm copies/hello-copy. Now rm will know what you mean!

Command summary

- ls : list files in a directory

- cp : copy files

- cat : show file contents

- mv : move or rename files

- rm : delete files

- mkdir : create directory

Why are commands like that?

Trisquel's ls, cp, mv, rm, cat and mkdir are GNU versions of UNIX commands. UNIX goes way back: all the way back to the 1970s! In those days, terminals were very slow and keyboards were heavy and tiring to type on. Cutting out letters where you could was something people appreciated very much!

More about the command line

Now you know a little about the command line. You've learnt how to list, copy, rename, move and delete files as well as create directories and new empty files.

There's much more to it than that, of course. There are hundreds of command-line programs that can do everything from rescaling images to archiving entire websites!

People still use the command line because it's so flexible. Multiple commands can be strung together in scripts and run over and over again as if they were just another command-line program themselves. Learning how to write scripts can be incredibly useful if you're running servers or writing your own software.

It may not have felt like it, but even learning a little about the command line is a big step. People are sometimes nervous about going deeper into GNU/Linux because the command line intimidates them. Now you know there's nothing to be afraid of!

How to learn more

We've come to the end of our tour of GNU/Linux. If you want to shut down and go back to Windows, open the Trisquel menu and choose 'Shut down'. Remember to remove your USB drive before turning on your computer again. All files you created during your session will be deleted.

The best way to learn more is to play around with Trisquel and see what it can do. Not long after this is published, there will be a section on Mission:Libre's website showing you how to connect Trisquel to the internet, download software and install it over Windows.

To learn more about the command line, you might like to read the coreutils manual at https://www.gnu.org/software/coreutils/manual. If you want help on a command while you're at the terminal you can use the man command to bring up the manual. To get help for ls, for example, type 'man ls'.

I can't recommend you buy non-free manuals, but if your library has access to books on Debian or Ubuntu they might be helpful. In true free software fashion, Trisquel is based on Ubuntu, which itself is based on Debian. There is more Trisquel-specific information at https://trisquel.info/en/wiki.

GNU/Linux has legions of fans for a very good reason. As you learn more about it, you'll see how great it is to trade in Windows and macOS for a system that respects your freedom.